-

Paesaggi fortificati, guardare senza essere visti

F.Collotti, G.Pirazzoli

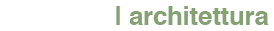

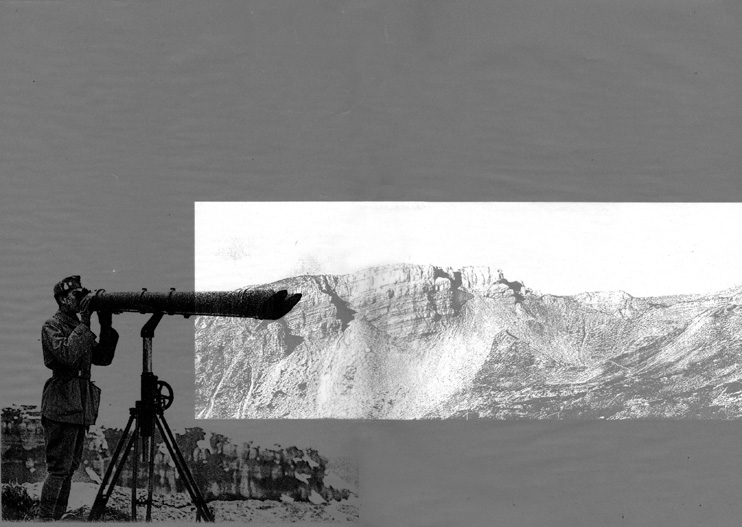

Pasubio, 1997Abbiamo dedicato circa 15 anni a progetti e realizzazioni circa la risignificazione di paesaggi fortificati attraverso operazioni di coltivazione architettonica dei luoghi. Alcuni musei ricostruiti tra gli enormi spessori di navi da guerra in pietra e cemento sepolte tra le montagne (Forte Belvedere a Lavarone), piccoli siti espositivi realizzati in quota, macchine ottiche e finestre ritagliate in lamiere navali di forte spessore, acidate alla maniera di reperti arrugginiti e orientate per misurare il paesaggio laddove – un tempo – i telemetri delle artiglierie traguardavano distanze. Non pittoresche riambientazioni con manichini, ma un portone rivestito come la corazza di un animale barbarico, pavimenti in battuto di cemento grezzo e larice (legno tecnico, non da arredatore), tabelle segnaletiche realizzate scavando con la fiamma spesse lastre metalliche: riportare l’acciaio ai monti, una sorta di risarcimento – forse del tutto irragionevole – per contrappasso alla sottrazione del ferro che qui fu depredato “per la patria” – e per un’altra guerra, la seconda – sul finire degli Anni Trenta.

Il tutto continuamente interrogandosi su alcune laconiche collezioni, necessariamente allestite con quel distacco che consente alle cose che recano ricordo di divenire oggetti il cui uso è sospeso, ostensi, profferti o semplicemente esposti, messi su un piedistallo o sotto un vetro, incorniciati a prender la giusta misura dal visitatore (una vicinanza irriducibile).

Nel paesaggio mediterraneo sul confine, e con i poveri strumenti del progetto – in ogni caso privi di effetti speciali – abbiamo ragionato su come la memoria sia essa stessa divenuta un bene culturale, al pari dei monumenti e dei luoghi. E a fronte dei nostalgici morbosi ricostruttori di rovine che imperversavano con le più varie ipotesi di imbalsamazione presso questi siti densi di tragedie passate, abbiamo cercato di contrapporre una ben più discreta idea di messa in opera della memoria capace di sottolineare i luoghi senza nasconderne l’esperienza nel corso del tempo (fatta di distruzioni, avvicendamenti, riconquista da parte della natura di paesaggi che furono per un giorno un mese un anno prima linea). E come per quello che è il più avanzato modo di conservare i resti archeologici serve ricercare una nuova espressività dei resti attraverso manufatti dedicati alla loro conservazione, così abbiamo in alcuni casi (Trambileno, arroccamenti a Forte Pozzacchio) perseguito un modo teso a far rivivere i manufatti stessi non già e non solo per la loro presenza, bensì anche in quanto fatti spaziali: con la consapevolezza che, se è al distratto visitatore della domenica che dobbiamo rivolgerci, dobbiamo essere anche capaci di aiutarne l’immaginazione e indirizzarne con la giusta forza l’occhio inesperto. -

Fortified Landscapes, seeing without being seen

F.Collotti, G.Pirazzoli

Pasubio, 1997We have dedicated around 15 years to creating and implementing projects based on giving back meaning to fortified landscapes through architectural interventions. Some museums built on the scale of great warships made of stone and cement (Forte Belvedere in Lavarone), small exhibition rooms built underground, optical machinery and windows made from thick, shipbuilding steel sheets, rusted like old exhibits to create the landscape where once the sights of the artillery watched out over the distance. Not quaint reconstructions with mannequins, but a large door armoured like a barbaric animal. Floors in rough cement and wood, signs made with flame on metal sheets: bringing back the iron to the mountains, some type of irrational compensation to recall the iron that was mined here for the ‘Fatherland’ and for the Second World War at the end of the Thirties. All of this entwined with a laconic collection, set up with that objectivity that makes the objects lose their sense of use, simply displayed, put on a pedestal or under glass, framed to demand the right moderation from the visitor (an inflexible proximity). In this Mediterranean border landscape without any special effects, we contemplated on how memory has in itself become a kind of cultural heritage, completely separate from monuments and places. Faced with the usual morbid, nostalgic redevelopers of ruins and their numerous ideas of embalming these sites which are full of past tragedies, we have tried to put forward a more discreet idea of a memorial which is able to lay emphasis on the places without hiding their history (destruction, alteration, nature’s reconquering of these places which were once for one day, one month or one year at the front line).And so, like the most advanced methods used for preserving archaeological exhibits, we need a new expression for these ruins through buildings dedicated to their conservation. Here, as in Trambileno and Fort Pozzacchio we have aimed at bringing the buildings themselves back to life, not only because of their actual structure but also due to their being. Well aware that we must aim at the distracted Sunday visitor, we must be able to ignite their imagination and guide their unskilled eye.